The ‘Arab Spring’s’ Missing Dimension – Views from the Countryside

Research Seminar held at the British Institute in Amman, 28-30 September 2013

This discussion seminar was held in partial fulfillment of a British Academy ‘Arab Spring’ Award to CBRL to investigate rural transformations leading up to and during the Arab Uprisings. Its main feature was the screening and associated discussion of a documentary film by Ray Bush (Leeds University) and Habib Ayeb (Université-Paris 8) on their fieldwork in Tunisia and Egypt in 2013 funded by the same award. The seminar brought together a group of researchers investigating agriculture, labour and environment, to provide feedback on the first cut of the film, as well as to share their own research experiences. The original BA award was made in early 2012, but fieldwork was postponed until 2013 due to the administrative and teaching responsibilities of Professors Bush and Ayeb. Fieldwork in Egypt was undertaken during the period of Muslim Brotherhood rule and Mohammed Morsi’s term as president, but the seminar took place after the military coup in June 2013 when the ancien régime returned under the leadership of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

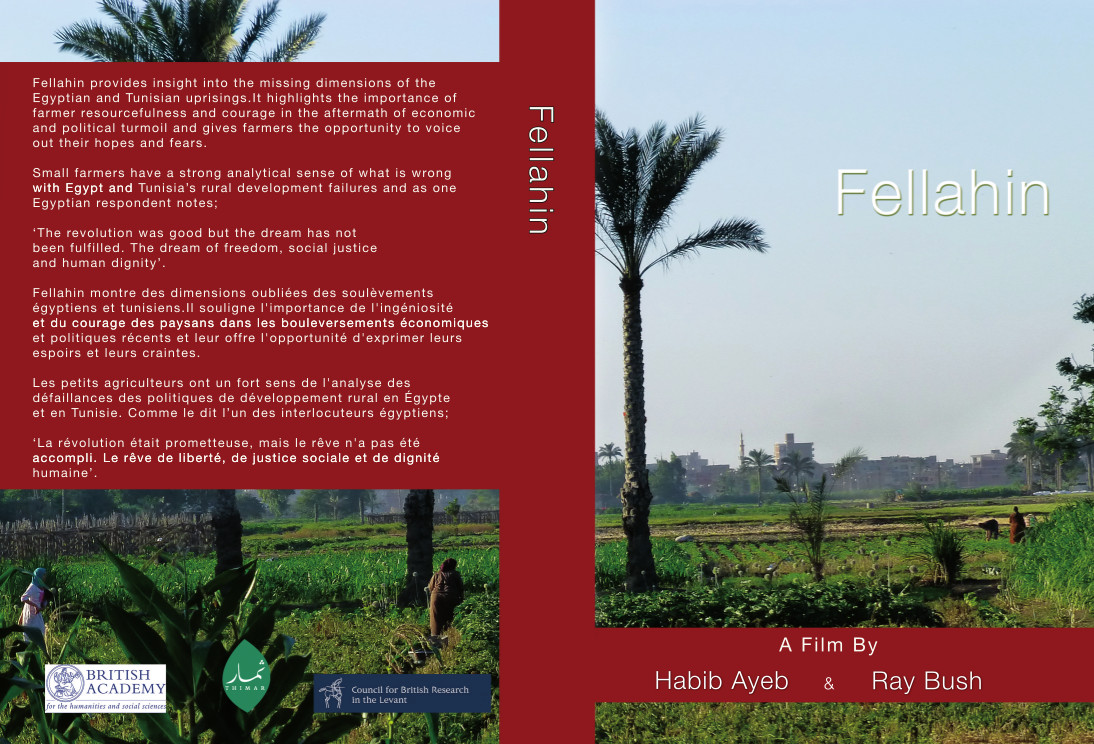

Bush and Ayeb’s film and their broader research project explore the position and perceptions of small farmers during the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings of 2010 and 2011. Persistent economic turmoil and political authoritarianism in both countries had an enormous impact in the countryside, and the film gives small farmers the opportunity to share both long-standing and immediate fears and concerns about farming, their families and politics. It also asks whether or not the farmers felt the declared aims of the uprisings had been achieved.

The film, at the time of the seminar called Forgotten Voices: Farmers and Revolution in Tunisia and Egypt, and now simply entitled Fellahin (‘Peasants’), was recorded in February 2013 in Tunisia and in May 2013 in Egypt. The film has three sections: Farmers and Farming; Uprising, and Fighting Back. These, in turn, introduce the farmers, give them the opportunity to voice what they understood by the periods of political transformation and turmoil as it affected them, and highlight the different forms and types of resistance in which they have engaged. The film combines interviews, voice-over and views of the locations in which the farmers live. In Tunisia, filming took place in the South in the Oasis Gabes and surrounding steppe, and in the North in the richer ecological areas of larger estate plantations in the district of Testour, not far from the capital, Tunis. Filming in Egypt took place in Cairo, Dakhalaya, Fayoum, and Alexandria, including farmers in the densely populated Delta, an oasis, and an inner city village, respectively.

The film shows a mismatch between rural political consciousness and agricultural strategy, strong peasant populism among small farmers, and a robust analytical sense of what went wrong to produce Egypt and Tunisia’s rural development failures. Since economic liberalization began in the late 1980s, small farmers have been ejected and expelled from ‘development’. Specifically, farmers in Egypt lament the continued lasting consequences of Law 96 of 1992 that ended rights in perpetuity for tenants and raised rents exponentially. Farmers in Tunisia are critical of the failure of policy to address access to potable water and improved and affordable irrigation. In both countries farmers are critical of larger landowners and merchants, who are viewed to have benefitted from decades of economic liberalization in the countryside, as well as of policymakers implementing strategies. While farmers do not feel that uprisings have improved their condition in any way, the film demonstrates a heightened willingness speak out and engage in resistance to the economic policies that are seen to have marginalized them. The Egyptian case provides a unique insight into one community’s mobilization around tamarod, the mass petition that contributed to the toppling of President Morsi. Mr. Morsi was not seen as a President able or willing to curb the power of landlords.

Yasmine Moataz’s (University of Cambridge) presentation, ‘Encountering the Egyptian State in Revolutionary Times’, picked up on the theme of land dispossession in Egypt while providing examples of cases where small farmers have contested their land claims through the judicial system. Carol Palmer (CBRL) and Waleed Gharaibeh’s (University of Jordan) paper on ‘The Politics of Development in Ghor al-Safi’ also explored a case of contested land claims following the redistribution of land as part of irrigation and industrial development of potash extraction during the 1980s and subsequently. Their team is also mapping landscape changes and interviewing local people, while employing GIS techniques in the analysis of socio-spatial change. Documenting agrarian changes though landscape analysis and ethnography was the subject of Martha Mundy (LSE), Rami Zurayk, Saker el Nour, and Cynthia Gharios’s (all AUB) talk, ‘The Palimpsest of Agrarian Change’, on the development of the village of Sinay in southern Lebanon.

Water was the focus of presentations by Mauro van Aken (Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca) on the Jordan Valley and Karim Eid Sabbagh (SOAS) on Lebanon. Both demonstrated how development agendas prioritize the interests of investor and state agencies over small farmers and communities. Karim Eid Sabbagh’s presentation, ‘A Political Ecology of Water Resource Management in Lebanon: an investigation of water sector reform’, discussed how reforms remain incomplete but fit well with neoliberal discourse (‘the playbook’) and existing power relations. In the Jordan Valley, Mauro van Aken’s perspective, entitled ‘Water Crisis, Marginality and Struggle for Resources in a High tech Environment – the Jordan Valley’, demonstrated that water is not only an economic resource but also a social one. Rami Zurayk gave a highly engaging presentation, ‘Power Games and Role Plays: The Red Lebanese resists in the Bekaa Plain’, on his and Helene Servel’s research. They showed a way in which farmers can make a living from the production of a crop (cannabis) for which premium prices can be attained, distribution is locally managed, and where resistance is also part of the motivation given the illegal status of the crop.

Myriam Ababsa’s (Ifpo Amman) talk, ‘Rural Land Issues in Contemporary Syria’, on agricultural production in the years leading up to the Syrian crisis, when there was drought in north-west Syria, and how this is playing out in the context of the current conflict, prompted intense discussion. Going much further back in time, Falestin Naili (Ifpo Amman) presented ‘History and Collective Memory of the Village of Artas in Palestine’, on the Christian missionary Baldensperger family from Alsace who lived in Ottoman Palestine in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and their surprisingly long-lasting impact.

The trip on the final day of the seminar allowed discussions to be continued, inspired by the dramatically beautiful landscape of the Jordanian Rift. Starting in Amman, descending the Wadi Shu'aib to the Jordan Valley, participants discussed climate, water catchment, refugees, and irrigation policies en route to and at the top of Tell Deir ‘Alla, an archaeological mound, in the village where Mauro van Aken had lived during his PhD research. While driving down half the length of the Jordan Valley and the whole of the Dead Sea, past luxury spa hotels, the industrial complexes of the Arab Potash Company to Ghor as Safi, subjects ranged from the dropping levels of the Dead Sea, to tourism, agriculture, and international business connections and politics. At Safi, Carol Palmer presented her team’s research and the history and development of Safi from Deir ‘Ain Abata, the Byzantine archaeological site commemorating Lot’s Cave. While some members of the party returned straight to the airport, a few visited the home of a female farmer, originally Egyptian, who has made a success of diversifying her production, has a local market (the Potash factory skilled workers) to whom she directly sells her produce, and maintains her own seeds stocks, with a small loyal team of workers.

In summary, film is an immensely powerful medium to document the human dimension of agrarian change currently facing the region. Initial film screenings of Fellahin will take place at the Tunisia Film Festival, ‘Douz Doc Days’ and at ‘Taking Soundings’ part of the Leeds City Forum for debate and engagement, both in October 2014. More activities of the Thimar group are reported on its website (www.athimar.org ), the development of which has also been supported by the British Academy Arab Spring Award.

Ray Bush and Carol Palmer