The Politics of Development in Ghor al-Safi, Jordan

Previously published in the CBRL Bulletin 2013, pp. 72-74

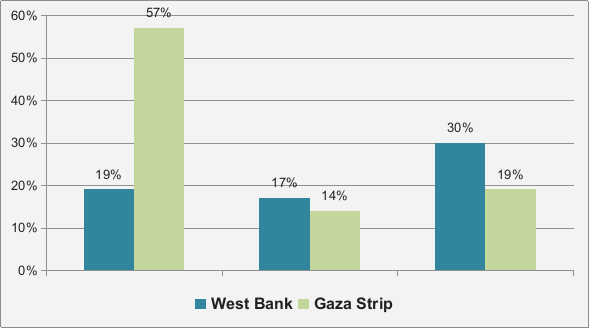

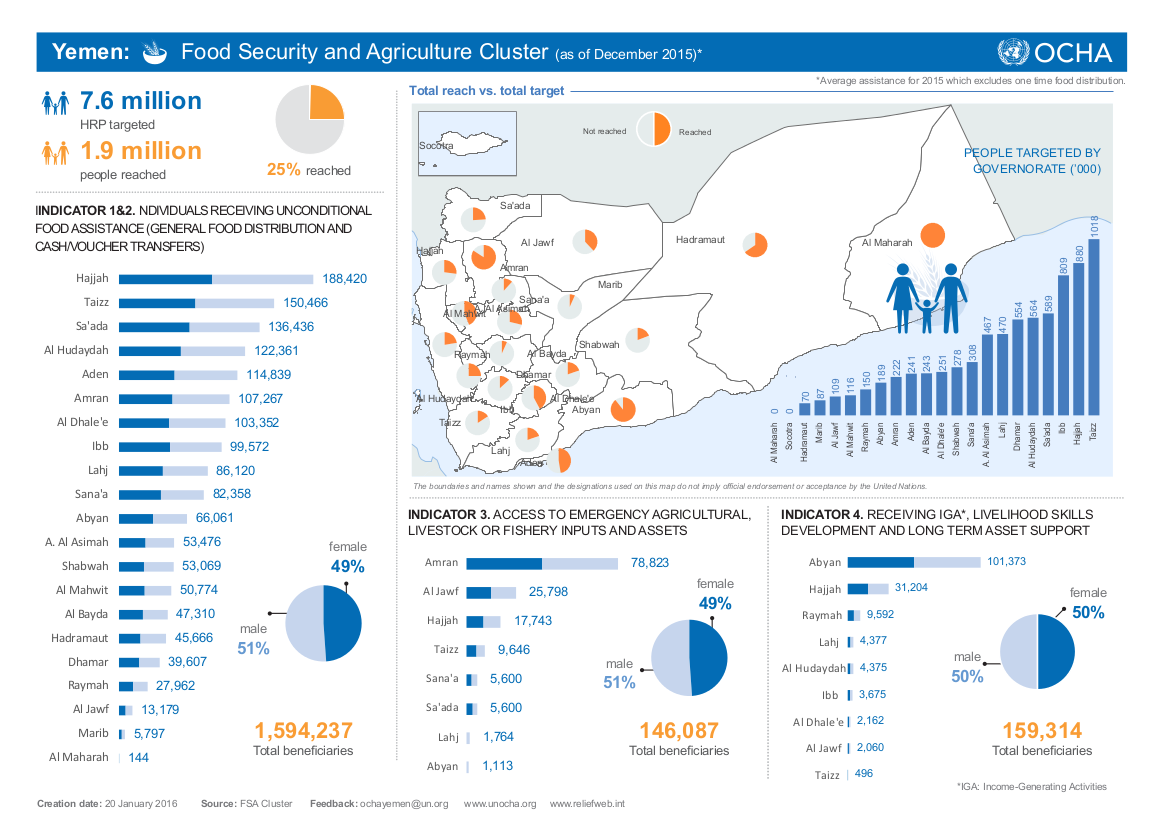

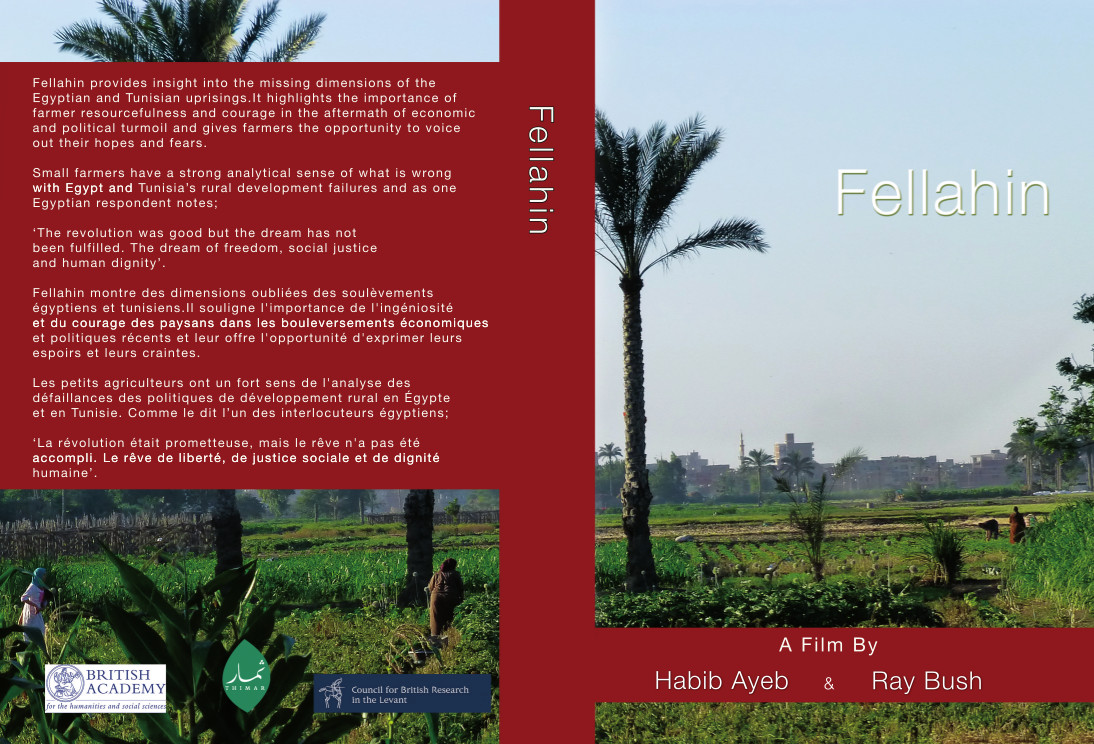

Agricultural development has long been a cornerstone of development policies worldwide. Yet, contemporary Arab regions have the greatest food ‘deficit’ of any region in the world and the trend shows no sign of abating. Indeed, current international economic policies appear to be advancing the phenomenon and contributing to a whole new critical debate on ‘food security’. Our project examines agricultural transformations in Ghor al-Safi in the context of the local community’s experience of those changes. While our research grew out of local concerns and connections, our insights have been much enhanced by our membership of a research community, the Thimar collective, including participation in a British Academy sponsored workshop at the British Institute Amman in January 2012, and research exchanges stemming from that meeting.

The Ghor, also Ghawr (‘depression’), in the southern Levant refers to the region of the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea, part of the Great Rift Valley. Ghor al-Safi is located on a fertile alluvial plain at the mouth of Wadi al-Hasa near the lower end of the Dead Sea. It is one of several communities along the eastern Dead Sea shore which are collectively referred to as the southern Ghor(s). Historically, the year-round residents of the hot and malaria-infested Ghor were considered a distinct group by both pastoral nomads and farmers of the higher grounds. They were, and still are, commonly referred to as Ghorani (also Ghawarneh), a term which invokes strong derogatory connotations related to their darker skin tone and underprivileged economic status. Like many rural people in Jordan in recent decades, their villages have grown into cement block towns, a life on the land has diversified into jobs in the army, government, industry and trade; yet, agriculture has remained an important component of family income, more so than in any other part of the country. The way agriculture is practiced is very much changed, however, following a very similar trajectory to the rest of the region: production of cereals and pulses has declined with a shift to the production of vegetables and fruits, products associated with capitalized production.

All of the land of the Ghor lies below sea level. Ghor al-Safi sits at the lowest place on Earth, c. 400 m below sea level, and is the hottest location in Jordan. Mild winter temperatures mean that the whole of the Ghor is a pleasant area in winter and early spring. For plants, higher temperatures mean an early growing season as well as fast growth and, for farmers, the potential for multiple crops in a year. But, to grow, agricultural plants require water and, in the high temperatures of the Ghor, a lot of water.

Ghor al-Safi, Jordan: contemporary irrigated agriculture at the lowest place on Earth. Photos by Carol Palmer.

View over Ghor al-Safi agricultural lands with the salt pans of the lower Dead Sea in the background.

The East Ghor Canal project (first phase, 1958–66) was the first major development project of the newly independent Kingdom of Jordan. This project channelled the waters leading into the Jordan River, principally the waters of the Wadi Yarmouk, for agriculture and human consumption. From the beginning, there were political dimensions to the irrigation projects in the Ghor that set the tone for development in the decades to come. The Wadi Yarmouk is a sensitive international border and the division of the water between Jordan, Syria and Israel, established principles that have largely continued to the present day. In the aftermath of 1948, the project also was intended to provide livelihoods to Palestinian refugees, as well as integrate them and build infrastructure for the young country. Starting in the north, the project continued in stages southwards, interrupted by the 1967 war when Jordan lost the West Bank. After this point, development of the project increasingly became bound up with political issues of stabilizing a long, problematic border. Only after 1994, and the signing of the peace treaty between Jordan and Israel, did these tensions ease significantly.

In 1977, the powerful Jordan Valley Authority (JVA) was founded and charged ‘with the integrated socio-economic development of the Jordan Valley’. By the mid 1980s, JVA development had reached the southern Ghors. According to the JVA, the aims were to make agriculture more efficient and profitable and improve living conditions and services for the community. Projects included the development of an underground system of water distribution for irrigation, the re-location of homes to adjacent non-productive land, and the restructuring of the road system. Major new areas were brought under cultivation, a process that continues to this day, largely at the expense of the hishe - wild, wooded areas and salt marshlands - which has largely disappeared. At the same time, and as an integral part of the development process, there was a major re-distribution of land.

Tomato 'sunrise' sign on the Dead Sea Highway along the approach to Ghor al-Safi, Jordan.

The JVA project was not the first modern irrigation project in Ghor al-Safi. In the 1940s, the irrigation network had been restored by the Palestine Potash Company (PPC), the first major modern mining operation in the Dead Sea region. The irrigation works were a part of a system which also carried fresh water from Wadi al-Hasa to the PPC main facilities at the bottom of Mount Sodom. Contacts with the PPC plant across the Dead Sea were cut following the 1948 war and, in 1956, the Arab Potash Company was established on the eastern shore of the sea, just north of Safi. As in the 1940s, the new mining operation required the drawing of water from Wadi al-Hasa. With major mining concessions operating of both sides of the sea, salt pans now cover the entire extent of the southern Dead Sea beyond the Lisan peninsula.

By the time of our first fieldwork in 2011/2012, agriculture in Safi was in crisis. The international markets that had made farming extremely profitable had disappeared; the culmination of a complicated series of events neatly reflecting the tumultuous recent history of the region up to the near closure of the Syrian border over the last couple of years. Local markets were flooded and produce prices plummeted. Massive increases in oil prices meant that oil derived inputs – piping, plastic mulch, fertilizers and transportation - were wildly expensive; indeed, water was the cheapest component. Only farmers using family labour and diversifying from the ubiquitous favourite, the tomato, stood a chance to break even. In general, farmers were making massive losses, unable to pay back their loans, and yet still planned to plant in the following season, gambling on making back their money. Investors and policy makers saw no future in farming; reckoning it to be a waste of water and much better to use this precious commodity for industry and tourism.

The people from Safi have changed too since the implementation of the 1980s irrigation scheme and development of the town and its infrastructure. They have become more integrated into the Jordanian economy and political life of the Kingdom through education, employment and the re-institution of the parliament. While painfully aware of historical injustice and continuing prejudice, the Ghorani have been able to identify themselves as patriotic Jordanians serving the country in roles in the army and public service. Pakistani, Egyptian and Syrian workers increasingly fill their places in the fields, both as labour and low-level management. Land allocation from the 1980s redistribution is contested, as concerns about property and representation in Parliament, on the JVA board and other positions of influence are debated as passionately – if not more - than the future of farming.

Tomato fields, water reservoir and the expanding town of Safi in the background.

JVA open water channel running along the Wadi Hasa. Remnants of an older water channel carved into the rock are to the

left. Older water channels are thought to date back to the mid twentieth century, the Mamluk and Roman periods.

Home belonging to a family of workers who originate from Pakistan. There exists a long-standing Pakistani community

in Jordan who work in agriculture and who are highly regarded as among the most skilled and best workers. Safi, Jordan.

Female worker planting 'fasuliya', common bean, in Safi, Jordan. Narrow black plastic piping runs under the mulch providing drip irrigation to the crop.

During planting, two to three 'fasuliya' beans are placed in each hole in the black plastic mulch, Safi, Jordan.